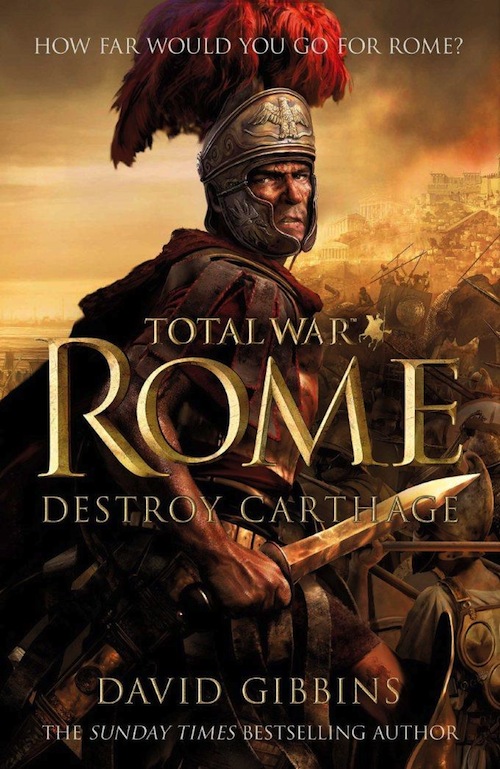

Check out Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage, the first in an epic series of novels by David Gibbins, available September 3rd from St Martin’s Press!

This is the story of Fabius Petronius Secundus—Roman legionary and centurion—and his rise to power: from his first battle against the Macedonians, that seals the fate of Alexander the Great’s Empire, to total war in North Africa and the Seige of Carthage.

Fabius’s success brings him admiration and respect, but also attracts greed and jealousy—the closest allies can become the bitterest of enemies. And then there is Julia, of the Caesar family—a dark horse in love with both Fabius and his rival Paullus—who causes a vicious feud.

Ultimately for Fabius, it will come down to one question: how much is he prepared to sacrifice for his vision of Rome?

PROLOGUE

On the plain of Pydna, Macedonia, 168 BC

Fabius Petronius Secundus picked up his legionary standard and stared out over the wide expanse of the plain towards the sea. Behind him lay the foothills where the army had camped the night before, and behind that the slopes that led up to Mount Olympus, abode of the gods. He and Scipio had made the ascent three days previously, vying with each other to be the first to the top, flushed with excitement at the prospect of their first experience of battle. From the snow-covered summit they had looked north across the wide expanse of Macedonia, once the homeland of Alexander the Great, and below them they had seen where Alexander’s successor Perseus had brought his fleet and deployed his army in readiness for a decisive confrontation with Rome. Up there, with the glare of the sun off the snow so bright that it had nearly blinded them, with the clouds racing below, they had indeed felt like gods, as if the might of Rome that had brought them so far from Italy was now unassailable, and nothing could stand in the way of further conquest.

Back down here after a damp and sleepless night the peak of Olympus seemed a world away. Arranged in front of them was the Macedonian phalanx, more than forty thousand strong, a huge line bristling with spears that seemed to extend across the entire breadth of the plain. He could see the Thracians, their tunics black under shining breastplates, their greaves flashing on their legs and their great iron swords held flat over their right shoulders. In the centre of the phalanx were the Macedonians themselves, with gilt armour and scarlet tunics, their long sarissa spears black and shining in the sunlight, held so close together that they blocked out the view behind. Fabius glanced along their own lines: two legions in the middle, Italian and Greek allies on either side of that, and on the flanks the cavalry, with twenty-two elephants stomping and bellowing on the far right. It was a formidable force, battle-hardened after Aemilius Paullus’ long campaigns in Macedonia, with only the new draft of legionaries and junior officers yet to see action. But it was smaller than the Macedonian army, and its cavalry were far fewer. They would have a tough fight ahead.

The night before, there had been an eclipse of the moon, an event that had excited the soothsayers who followed the army, signalling a good omen for Rome and a bad one for the enemy. Aemilius Paullus had been sensitive enough to the superstitions of his soldiery to order his standard-bearers to raise firebrands for the return of the moon, and to sacrifice eleven heifers to Hercules. But, while he had sat in his headquarters tent eating the meat from the sacrifice, the talk had not been of omens but of battle tactics and the day ahead. They had all been there, the junior tribunes who had been invited to share the meat of sacrifice on the eve of their first experience of battle: Scipio Aemilianus, Paullus’ son and Fabius’ companion and master; Ennius, a papyrus scroll with him as always, ready to jot down new ideas for siege engines and catapults; and Brutus, who had already fought wrestling matches with the best of the legionaries and was itching to lead his maniple into action. With them was Polybius, a former Greek cavalry commander who had the ear of Paullus and was close to Scipio—a friendship that had been forged in the months since Polybius had been brought as a captive to Rome and been appointed as an instructor to the young men, even teaching Fabius himself how to speak Greek and some of the wonders of science and geography.

That evening, Fabius had stood behind Scipio, listening keenly as he always did. Scipio had argued that the Macedonian phalanx was outmoded, a tactic from the past that was over-reliant on the spear and left the men vulnerable if an enemy got within them. Polybius had agreed, adding that the exposed flanks of the phalanx were its main weakness, but he had said that theory was one thing and seeing a phalanx in front of you was another: even the strongest enemy would baulk at the sight, and the phalanx had never been defeated before on level ground. Their chief hope was to shake the phalanx out of its formation, to create a weakness in its line. From his vantage point now, looking across at the reality, Fabius was inclined to side with Polybius. No Roman legionary would ever show it, but the phalanx was a terrifying sight and many of the men along the line girding themselves for battle must have felt as Fabius did, his breathing tight and a small flutter of fear in his stomach.

He looked at Scipio now, resplendent in the armour left to him by his adoptive grandfather Scipio Africanus, legendary conqueror of Hannibal the Carthaginian at the Battle of Zama thirty-four years before. He was the younger son of Aemilius Paullus, only seventeen years old, a year younger than Fabius, and this would be their first blooding in combat. The general stood among his staff officers and standard-bearers a few paces to the left, with Polybius among them. As a former hipparchus of the Greek cavalry, experienced in Macedonian tactics, Polybius was accorded a special place among the general’s staff, and Fabius knew he would be wasting no time telling Aemilius Paullus how he should run the battle.

The pendant on top of the standard fluttered in the breeze, and Fabius looked up at the bronze boar, symbol of the first legion. He gripped his standard tightly, and remembered what he had been taught by the old centurion Petraeus, the grizzled veteran who had also trained Scipio and the other new tribunes who were preparing for battle today. Your first responsibility is to your standard, he had growled. As standard-bearer of the first cohort of the first legion he was the most visible legionary in his unit, the one who provided a rallying point. Your standard must only fall if you fall. Secondly, he was to fight as a legionary, to close with the enemy and to kill. Thirdly, he was to look after Scipio Aemilianus. The old centurion had pulled him close before he had seen them off on the ship at Brundisium for the crossing to Greece. Scipio is the future, the centurion had growled. He is your future, and he is the future I have spent my life working for. He is the future of Rome. Keep him alive at all costs. Fabius had nodded; he knew it already. He had been watching out for Scipio ever since he had entered his household as a boy servant. But out here, in front of the phalanx, his promise seemed less assured. He knew that if Scipio survived the initial clash with the Macedonians he would go far ahead, fighting on his own, and that it would be the skills in combat and swordplay taught by the centurion that would keep him alive, not Fabius running after him and watching his back.

He gazed up at the sky, squinting. It was a hot June day, and he was parched. They were facing east, and Aemilius Paullus had wanted to wait until it was late enough in the day for the sun to be over them, not in the eyes of his troops. But up here on the ridge they were away from a good water supply, with the river Leucos behind enemy lines in the valley below. Perseus would have understood this as he ordered his phalanx to advance slowly through the day, knowing that the Romans would be tormented by thirst, waiting until his own troops did not have the sun in their eyes after it had passed over the mountains to the west.

Fabius stared at the spider in the long grass that he had been watching earlier to calm his mind, to keep his nerves for the coming battle. It was large, as wide as the palm of his hand, poised on its threads between the few yellow stalks of corn stubble that had not yet been trodden down by the soldiers. It seemed inconceivable that such a large spider should hang by such delicate threads on two stalks of corn, yet he knew that the threads had great strength and the stalks were dried and hardened by the summer sun, making the stubble so rigid that it grazed the unprotected parts of their legs. Then he saw something, and knelt down, watching carefully. Something was different.

The web was shaking. The whole ground was shaking.

He stood up. “Scipio,” he said urgently. “The phalanx is moving. I can feel it.”

Scipio nodded, and went over to his father. Fabius followed, careful to keep his standard high, and stood outside the group, listening while Polybius engaged the other staff officers in a heated discussion. “We must not engage the phalanx frontally,” he said. “Their spears are too close together, and are designed to pierce the attackers’ shields and hold them fast. Once the attackers are without shields, then the second line of the phalanx will dart out and cut them down. But the strength of the phalanx is also its weakness. The sarissa spears are heavy and unwieldy and difficult to swivel in unison. Get among them when they are still massed together, and they are yours. The short Greek swords are no match for the longer Roman gladius.”

Aemilius Paullus squinted at the phalanx, shading his eyes. “That’s why our cavalry are on either wing, with the elephants. Once the phalanx begins its final assault, I will order them to charge and outflank it.”

Polybius shook his head vehemently. “I advise against it. The Macedonian spearmen on the flanks will be ready for that. You need to go for the middle of the line, to break it up in several places, to create gaps and exposed flanks where it’s difficult for them to manoeuvre. Infantry alone can’t do that by frontal assault, as they’ll be stopped by the spears. You need to use your elephants, several of them together in four or five places a few hundred paces apart. The elephants have frontal armour and even if they’re pierced they’ll carry on for many paces with the momentum of their huge weight and smash through the line before they fall. If the legionaries follow closely behind, they will pour through the gaps and create four or five separate assaults, eating away at the exposed flanks. The phalanx will collapse.”

Aemilius Paullus shook his head. “It’s too late for that. The elephants are mustered in one squadron on the right flank, and that’s where they’ll attack. They have strength in numbers, and a massed elephant charge will terrorize the enemy. The cavalry will follow and sweep round the rear of the phalanx.”

“And the infantry?” Polybius persisted. “Even if you order your infantry to follow after the cavalry at double pace they would never make it to the right flank and around the back of the phalanx in time to consolidate the gains made by the cavalry. The phalanx will have had time to form a defensive line to the rear. Our own line will have been gravely weakened.”

“There can be no change of plan, Polybius,” Aemilius Paullus said, squinting ahead. “The phalanx is beginning to move again. And I promised the leader of the Paeligni in our front line that they would lead the assault. The die is cast.”

Polybius turned away, exasperated. Scipio went up to him and put a hand on his shoulder, pointing at the gap between the two armies. “Look at the terrain,” he said quietly. “The phalanx is at the head of the valley leading up from the sea, on relatively level ground where they can form a continuous line. We’re in the foothills of the mountains. As the phalanx marches forward, the line will be broken up as they encounter the rough ground and gullies where the valley ends and the slope rises ahead of them. As long as we are ready to pour legionaries into those gaps, all we have to do is keep our nerve and wait for them. The terrain will do the job for us.”

Polybius pursed his lips. “You may be right. But it will be too late to stop the Paeligni from making their charge. They are Latin allies and brave men, but they are not equipped or disciplined as legionaries and they will be cut down. And once your father sees the result, it may cause him to use restraint and keep the rest of the line from following.”

“My father is an excellent reader of terrain,” Scipio said pensively. “Your strategy is sound, but we cannot redeploy the elephants now. By waiting here for the phalanx to come to us, the same effect of breaking up the line will be achieved. A suicidal charge by the Paeligni may be a sacrifice worth making, as it will boost the confidence of the phalanx and make them less cautious about keeping their line tight as they encounter rough terrain. And once we send legionaries into those gaps, my father can use the cavalry and elephants as he planned to outflank the phalanx and come up on their rear, at a time when they will be focused on confronting the incursions into their line from the front and will be less well organized for creating a rear defence. If the legionaries keep steady, the Macedonians will be routed.”

“The resolve of the legionaries is one thing that cannot be doubted,” Polybius said. “This is the best army that Rome has ever fielded.”

Fabius saw a shimmer go along the spears of the phalanx as they locked together in close formation and moved slowly forward. He looked beyond the second legion to his right and saw the Paeligni, tough warriors from the mountain valleys to the east of Rome who were always given a loose rein to keep them loyal. They wore bronze skullcaps and quilted linen chest armour and carried vicious wide-bellied slashing swords, and when they charged they bellowed like bulls. A rider appeared from their midst and galloped out of the line, straight towards the phalanx, pulling left just before reaching the spears and hurling a javelin with a banner into the midst of the Macedonians, then turning and galloping back towards the Roman lines. The charge was now inevitable. The Paeligni were sworn to recover their standard whatever the cost, and before a battle to prove their intentions to their Roman commanders they always threw it into the enemy lines.

Polybius suddenly turned and took the bridle of his horse from his equerry. “There is one thing I can do.” He turned to his sword-bearer and took his helmet, an old Corinthian type with a large nose guard and cheekpieces that concealed his face almost completely. He put it on, pulled the strap tight under his chin and then leapt expertly onto the horse, leaning forward and patting its neck as it stomped and whinnied. He pointed to his shield and his equerry handed it up to him, a circular form embossed at the centre with a thick rim of polished steel around the edge. He put his left forearm through the two leather straps at the back and held it tight to his side, keeping his right hand on the neck of the horse. There was no saddle, and he had cast off the bridle; Fabius remembered Polybius telling him how he had learned to ride bareback as a boy and always charged into battle that way. The horse reared up on its hind legs, its eyes wide open and its mouth chomping and foaming, knowing what lay ahead.

Scipio looked up at him, alarmed. “What are you going to do? You haven’t even got a weapon.”

Polybius raised his shield. “The edge of this is as sharp as a sword blade. We trained to use our shields as weapons under the riding master at Megalopolis when I was your age. Another weakness of the phalanx is that the spears are held so rigidly together that they can be broken by riding at them along the line.”

“You’ll be cut down,” Scipio exclaimed. “You’re too valuable to die like that. You’re a historian. A strategist.”

“I was commanding officer of the Achaean cavalry before I was sent as a captive to Rome. I was your age, leading my first cavalry charge when you were barely able to walk. But you know where my allegiance lies now. I can’t bear to see a Roman ally charge to their deaths without giving them a chance, and I’m the only one here who knows how to do this.”

“If the Macedonians unhorse you and take off your helmet and recognize you as a Greek, you’ll be hacked to death.”

“The sarissae are not throwing spears, remember. As long as I stay just beyond their reach and my horse Skylla does her duty, I will survive. Ave atque vale, Scipio. Hail and farewell.” Polybius dug his shins into the horse and it thundered off, kicking up a cloud of dust that momentarily obscured the view. As it cleared, Fabius could see the reason for his abrupt departure. The Paeligni had already begun their charge, bounding forward like wild dogs, making a noise like a thousand rushing torrents. They were running at astonishing speed, and the distance between them and the phalanx had already narrowed. Fabius could see Polybius making for the gap, his shield held out diagonally to the left, charging in a swirl of dust. Another horse had followed, riderless, breaking away from the Roman lines until it overtook Polybius and disappeared into the storm of dust. For a horrifying moment it seemed as if he would not make it in time, as if the gap would close and he would hurtle among the horde of Paeligni warriors. But then he was gone, and all Fabius could see was a streak of silver along the line of Macedonian spears, as if a wave were passing along it. The spears in front of the Paeligni were broken and in disarray, leaving the phalanx vulnerable and exposed. Then the Paeligni were among them, their huge curved swords scything and slashing, their yells and screams rending the air. Fabius could see no way that Polybius could have survived to come out the other side; he closed his eyes for a moment and mouthed the brief words of prayer that his father had taught him to say at the passing of a fellow soldier in battle.

“Look to your front, legionary,” Scipio ordered, his voice hoarse with tension. He stood beside Fabius with sword drawn, staring ahead. While they had been watching Polybius the rest of the phalanx on either side had moved rapidly forward, exactly as Scipio had predicted. They were no more than two hundred paces away now, but the line directly in front of Fabius and Scipio had been broken as the Macedonians negotiated a dried-up watercourse caused by melt-water run-off from the mountain, widening into a gulley with sides about the height of a man.

“There’s our chance,” Scipio said. “We need to get at them while they’re in the gully, before they close up the line again.”

Fabius glanced at Aemilius Paullus, who had put his helmet on and stood among his other staff officers with sword drawn. Behind them the maniples of the first legion stood in full battle array, the centurions marching up and down in front of them, bellowing orders to keep in position, to wait for the order, to do what legionaries do better than any others, to kill the enemy at close quarters, to thrust and slash and draw blood and show no mercy.

Scipio put his hand on Fabius’ shoulder. “Until we meet again, my friend. In this world or the next.”

As Scipio turned to him he looked young, too young for what they were about to do, and Fabius had to remember that Scipio was only seventeen years old, a year younger than he himself was; it was an age difference that had given him an edge of authority over Scipio when they had been boys, which made Scipio still listen to him even though they were divided by rank and class, but now the difference was irrelevant as they stood as one with six thousand other legionaries ready to do their worst. Fabius replied, his voice hoarse, sounding strangely disembodied, “Ave atque vale, Scipio Aemilianus. In this world or the next.”

He grasped his standard tightly and drew his sword. He saw Scipio catch his father’s eye, and Aemilius Paullus nodding. Time suddenly seemed to slow down; even the increasing crescendo of noise seemed drawn out, distant. Fabius watched Scipio run to the left, out in front of the first maniple, and then turn to the lead centurion, leaning forward and bellowing at him, then looking back to face the enemy, the sweat flicking off his face. He raised his sword and shouted again, and the legionaries behind him did the same—a deafening roar that seemed to drown out all other sensations. Fabius realized that he was doing the same, yelling at the top of his voice and shaking his blade in the air.

He tried to remember what the old centurion had told him about battle. You will see nothing but the tunnel in front of you, and that tunnel will become your world. Clear that tunnel of the enemy, and you may survive. Try to see what goes on outside the tunnel, take your eye off those who have their eyes on you, and you will die.

Scipio began to run. The whole ground shook as the legionaries followed. Fabius ran too, not far behind Scipio, parallel with the primipilus of the first legion. The gap in the phalanx was narrowing as the Macedonian soldiers divided by the gully realized their mistake and ran forward to the head of the gully to join up again; but in so doing they extended their line along the sides, some of them swinging their spears around to protect the flanks and others surging ahead to try to close the gap.

Fabius was breathing hard and could feel the dryness of his throat. Scipio was no more than a hundred paces from the phalanx now. Suddenly an elephant appeared in a swirl of dust from the right, a Macedonian spear stuck deep in its side, out of control and dragging the mangled corpse of a rider behind. It saw the gulley and veered right into the phalanx, trampling bodies that exploded with blood as it crashed through the lines and then tripped and rolled to a halt inside the gully, creating further disarray in the Macedonian ranks. Following the elephant came the first of the Paeligni warriors, screaming and waving their swords as they hurtled into the Macedonian line. The first one was skewered on a spear but kept running forward into the shaft until he reached the Macedonian soldier, beheading him with a single swipe of his sword before falling dead. The same happened all along the line, suicidal charges that opened more and more gaps in the phalanx, allowing the mass of legionaries who followed to break through and get behind the front ranks of spearmen, using their thrusting swords to bring down the Macedonians in their hundreds.

In seconds, Fabius was among them. He was conscious of passing through the line of spears and swerving to avoid the dying elephant, and then seeing Scipio stabbing and hacking ahead of him. He swept his sword down across the exposed ankles of the line of spearmen beside him, leaving them screaming and writhing on the ground for the legionaries who followed to finish off. Then he was close behind Scipio, thrusting and slashing, going for the neck and the pelvis, his arms and face drenched in blood, always keeping the standard raised. A huge Thracian came behind Scipio’s back and whipped out a dagger, but Fabius leapt forward and stabbed his sword up through the back of the man’s neck into his skull, causing his eyeballs to spring out and a jet of blood to arch from his mouth as he fell. All around him the din and smell was like nothing he had experienced before: men screaming and bellowing and retching, blood and vomit and gore spattering everywhere.

Then Fabius was conscious of another noise, of horns sounding—not Roman trumpets but Macedonian mountain horns. The fighting suddenly slackened, and the Macedonians around him seemed to melt away. The horns had sounded the retreat. Fabius staggered forward to Scipio, who was leaning over and panting hard, holding his hand against a bloody gash in his thigh. The combat had only lasted minutes, but it felt like hours. Around them the legionaries passed forward over the mound of bodies where the Macedonian line had been, slashing and thrusting to finish off the wounded, like a giant wave crashing over a reef and disappearing to shore. Scipio stood up and leaned on Fabius, and the two of them surveyed the carnage around them. As the dust settled, they could see the cavalry pouring around the flanks and pursuing the retreating Macedonians far ahead, a rolling cloud of death that pushed the enemy back into the plain and towards the sea.

Fabius remembered another thing the old centurion had told him. The tunnel that had been his world, the tunnel of death that seemed to have no end, would suddenly open up and there would be a rout, a massacre. There would seem no logic to it, but that was how it happened. This time, it had gone their way.

Aemilius Paullus came down the slope towards them, his helmet off, followed by his standard-bearers and staff officers. He made his way over the mangled bodies and stood in front of Fabius, who did his best to come to attention and hold his standard upright. The general put his hand on his shoulder and spoke. “Fabius Petronius Secundus, for never letting the standard of the legion drop and for staying at the head of your maniple, I commend you. And the primipilus said he saw you save the life of your tribune by killing one of the enemy while still holding the standard high. For that I award you the corona civica. You have made your mark in battle, Fabius. You will continue to be the personal bodyguard of my son, and one day you may earn promotion to centurion. I fought beside your father when I was a tribune and he was a centurion, and you have honoured his memory. You may go back to Rome proud.”

Fabius tried to control his emotions, but felt the tears streaming down his face. Aemilius Paullus turned to his son. “And as for the tribune, he has proven himself worthy to lead Roman legionaries into battle.”

Fabius knew there could be no greater reward for Scipio, who bowed his head and then looked up, his face drawn. “I congratulate you on your victory, Aemilius Paullus. You will be accorded the greatest triumph ever seen in Rome. You have honoured the shades of our ancestors, and of my adoptive grandfather Scipio Africanus. But I now have another task. I must prepare the funeral rites for Polybius. He was the bravest man I have known, a warrior who sacrificed himself to save Roman lives. We must find his body and send him to the afterlife like his heroes, like Ajax and Achilles and the fallen of Thermopylae.”

Aemilius Paullus cleared his throat. “Fine, if you can persuade him to leave aside the far more interesting business of interviewing Macedonian prisoners of war for the account he intends to write of this battle for his Histories.”

“What? He’s alive?”

“He carried on riding to the right flank of the phalanx, turned back to our lines, and charged again at the head of the cavalry, and then came back to collect his scrolls so that he could write an eyewitness account while it was still fresh in his mind. That is, before he had a sudden brainwave and galloped off by himself to find King Perseus, wherever he might be hiding, to get his take on the battle.”

“But he couldn’t be bothered to stop and tell his friends that he was alive?”

“He had far more important things to do.”

Scipio shook his head, then wiped his face with his hand. He suddenly looked terribly tired.

“You need water,” Fabius said. “And that wound needs to be tended.”

“You too are wounded, on your cheek.”

Fabius reached up with surprise and felt congealed blood from his ear to his mouth. “I didn’t feel it. We should go to the river.”

“It runs red with Macedonian blood,” Aemilius Paullus said.

“It’s everywhere.” Scipio looked at the drying blood on his hands and forearms and on his sword. He squinted at his father. “Is this an end to it?”

Aemilius Paullus looked over the battlefield towards the sea, and then nodded. “The war with Macedonia is over. King Perseus and the Antigonid dynasty are finished. We have extinguished the last remnant of the empire of Alexander the Great.”

“What does the future hold for us?”

“For me, a triumph in Rome like no other in the past, then monuments inscribed with my name and the name of this battle of Pydna, and then retirement. This is my last war, and my last battle. But for you, for the others of your generation, for Polybius, for Fabius, for the other young tribunes, there is war ahead. The Achaean League in Greece to the south will need subduing. The Celtiberians in Spain were stirred up when Hannibal took them as allies, and will resist Rome. And, above all, Carthage remains—unfinished business even after two devastating wars. It will be a hard road ahead for you, with many challenges to overcome, with Rome herself sometimes seeming an obstacle to your ambitions. It was so for myself and for your adoptive grandfather, and will be ever thus as long as Rome fears her generals as much as she lauds their victories. If you are to succeed and stand as I am victorious on a field of battle, you must show the same strength of determination to remain true to your destiny as you have shown strength on the field of battle. And for you, the stakes are even higher. For those of your generation, for those of you who are young tribunes today, those whom we in Rome concerned for the future have nurtured and trained, your future will not be to stand on a battlefield as we are today at Pydna or as your grandfather did at Zama, to see the glory of triumph and then retirement. Your future will be to look away from Rome, to see from your battlefield a horizon that none of us has seen before, and to be tempted by it. The empire of Alexander the Great may be gone, but a new one beckons.”

“What do you mean?” said Scipio.

“I mean the empire of Rome.”

From Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage by David Gibbins. Copyright © 2013 and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.